The Passionate Artist: How Emile Galle Glass Art Reshaped An Industry

Collectors today have so many antique art glass styles to choose from that it’s easy to forget how contemporary the concept of ‘art glass’ really is. Yet a brief look through the types of glass popular with collectors today—such as vaseline glass, depression glass, and carnival glass—reveals that many prized pieces were once intended purely for practical or decorative use.

Collectors today have so many antique art glass styles to choose from that it’s easy to forget how contemporary the concept of ‘art glass’ really is. Yet a brief look through the types of glass popular with collectors today—such as vaseline glass, depression glass, and carnival glass—reveals that many prized pieces were once intended purely for practical or decorative use.

We owe the idea of creating glass for art’s sake primarily to one man: Emile Galle. Like his revolutionary contemporaries Gustav Klimt, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and Oscar Wilde, Galle believed strongly in both a unification of the arts (i.e., abolishing the hierarchy that stated ‘high’ arts like painting and sculpture were intrinsically superior to crafts like glassmaking) and the idea of ‘art for art’s sake.’

The artists, writers, and craftsmen of the Art Nouveau movement knew that art does not need a ‘reason’ to exist—it requires no moral message, no explicit purpose—it only needs to ‘be.’

Though the idea that beauty is in itself elevating and worthwhile may not seem surprising to us today, prior to Galle and his peers it was lost amidst the formalised ‘clutter’ of Victorian society.

Though the idea that beauty is in itself elevating and worthwhile may not seem surprising to us today, prior to Galle and his peers it was lost amidst the formalised ‘clutter’ of Victorian society.

Between the automated practicality of the industrial age and the influence of rigidly structured art academies, art, design, and quality craftsmanship had all begun to stagnate.

Reclaiming these creative domains in order to unify them as one style—a style that could be used to create a complete artistic living environment—required an intense spirit of exploration. It necessitated a journey around the world, through time, and between disciplines. There was perhaps no more thorough traveller of this road than Emile Galle.

Emile Galle: The Father Of Nouveau Art Glass

Born in the French town of Nancy in 1846, Emile Galle was introduced to glassmaking very early in life. His father, Charles Galle, was a well-known faience and traditional glassmaker with his own Galle Glass factory. From a young age, Emile was schooled in painting faience, as well as cutting and enamelling Charled Galle glassware.

Born in the French town of Nancy in 1846, Emile Galle was introduced to glassmaking very early in life. His father, Charles Galle, was a well-known faience and traditional glassmaker with his own Galle Glass factory. From a young age, Emile was schooled in painting faience, as well as cutting and enamelling Charled Galle glassware.

Emile quickly figured out that his ambitions extended far beyond the confines of Nancy, however. As a young man, he extended his studies to include botany, chemistry, philosophy and art, before further refining his glassmaking techniques at Meisenthal. After a stint spent working with his father at their family factory in 1867, Galle branched out even further, travelling extensively around Europe to expand his knowledge of glassmaking. Emile left no stone unturned, so avid was his quest to perfect his craft; he visited numerous museums and met with other designers regularly on his journeys. From the Oriental collection at the Victoria and Albert museum in London he learned of eastern enamelling and from designer Eugene Rousseau he was taught the joy of cameo—two techniques that would fuel his own creative efforts upon his return to Nancy.

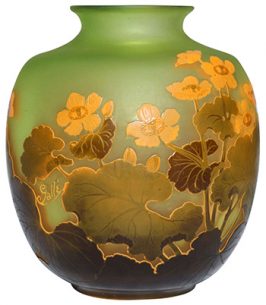

As Galle’s independent career found firm footing, he experimented freely with both the artistic and technological innovations of his age. He enamelled clear glass, crafted cameo glass, and combined heavy opaque etched glass with the light, airy Japanese styles beloved by Art Nouveau scholars. Into each vessel he always carved or sealed a single poetic sentence, balancing the very human art of literature with design work that was clearly inspired by the raw fundamentals of nature: Light and dark, birth and death, growth and decay. Many believe that the political and intellectual firmament of the late Victorian era also provided a backdrop to Galle’s innate genius, inflaming its intensity and accentuating Galle’s love of contrasts.

As Galle’s independent career found firm footing, he experimented freely with both the artistic and technological innovations of his age. He enamelled clear glass, crafted cameo glass, and combined heavy opaque etched glass with the light, airy Japanese styles beloved by Art Nouveau scholars. Into each vessel he always carved or sealed a single poetic sentence, balancing the very human art of literature with design work that was clearly inspired by the raw fundamentals of nature: Light and dark, birth and death, growth and decay. Many believe that the political and intellectual firmament of the late Victorian era also provided a backdrop to Galle’s innate genius, inflaming its intensity and accentuating Galle’s love of contrasts.

Like many great geniuses, Galle knew how to embrace accidents and the fruits of chance when creating his Nouveau art glass. His pieces, while stunningly beautiful, are enriched by unconventional quirks. Patterns of air bubbles and unpredictable dashes of colour lend inimitable character to many of his works. He was also fond of eclectic motifs, such as insects and wilting flowers. Strange as these designs must have seemed to some of Galle’s prim Victorian audience, they soon caught on; by 1873, Galle glass was very successful and Galle opened up his own studio (in addition to taking over his father’s glass and ceramics factory).

In 1878, Galle was formally honoured for his contributions to the world of Nouveau art glass when he was awarded the Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition. But this award—and the more widespread popularity that came with it—were not what preoccupied Galle primarily. Instead, his trip to the Exhibition saw him develop a fascination with the cameo glass of Englishmen Locke and Northwood.

In 1878, Galle was formally honoured for his contributions to the world of Nouveau art glass when he was awarded the Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition. But this award—and the more widespread popularity that came with it—were not what preoccupied Galle primarily. Instead, his trip to the Exhibition saw him develop a fascination with the cameo glass of Englishmen Locke and Northwood.

Back in his Nancy studio, Galle glass drew heavily on Galle’s training in chemistry to further refine his ability to work with cameo glass, which he would eventually combine with metallic foils for a wholly unique look. At the same time, his newfound love for marquetry designs (used in making furniture at the time) propelled him to open a woodworking shop. Glass would, however, remain his signature medium: As the 1880s progressed, his nouveau art glass was given accolade after accolade. Highlights included his celebrated exhibition of 300 pieces at the 1884 Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and the 1889 and 1890 Paris Exhibitions, which saw his work receive two awards and the sincerest form of flattery: Imitation. Fellow Nancy natives the Duam brothers began to produce glass in Galle’s style and a string of other minor glassmakers soon followed suit. Meanwhile, authentic Galle pieces were increasingly finding homes in museums and art collections.

With wealth and success came freedom: In 1894, Galle built a new manufacturing plant in Nancy (named the ‘Cristallerie d’Emile Galle’) and began to create his own glassware designs. These were faithfully replicated by his dedicated team of 300 employees, with Galle monitoring progress every step of the way. At the Cristallerie, Galle also expanded his chemical mastery of glass even further, devising never-before-seen techniques like mixing metallic oxides with glass and suspending them in oil to create a wonderfully lustrous finish. He even revived an 8th century BC technique known as ‘wheel cutting’ to create faceted table lamps. So revolutionary was Galle Glass that he was eventually granted the French Legion of Honour.

With wealth and success came freedom: In 1894, Galle built a new manufacturing plant in Nancy (named the ‘Cristallerie d’Emile Galle’) and began to create his own glassware designs. These were faithfully replicated by his dedicated team of 300 employees, with Galle monitoring progress every step of the way. At the Cristallerie, Galle also expanded his chemical mastery of glass even further, devising never-before-seen techniques like mixing metallic oxides with glass and suspending them in oil to create a wonderfully lustrous finish. He even revived an 8th century BC technique known as ‘wheel cutting’ to create faceted table lamps. So revolutionary was Galle Glass that he was eventually granted the French Legion of Honour.

In his later years, Galle led the elite ‘Ecole de Nancy’, which was intended to promote the Art Nouveau style and encourage a union between art and industry. This school was not for amateurs: Only those who were already considered master artisans could apply. The Daum brothers, along with furniture makers Victor Prouve and Louis Majorelle and the skilled potter Hesteaux, were some of the Ecole’s most famous students.

By the time Emile Galle passed away in 1904 (an untimely end brought about by leukemia) he was a certified icon—Not only of glassmaking, but also of his age. He embodied the passionate curiosity, technological mastery, and keen aesthetic sense that was the epitome of fin de siecle greatness. Though his works ceased to be reproduced in 1936, they live on in many of the world’s most distinguished museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian, and the Louvre.